In 1896 Dr. Joseph H. Romig traveled to Bethel, Alaska, and opened the first doctor’s office and hospital west of Sitka, at a time when there were very few non-native people living in remote southwest Alaska. Four decades later a book would be written about the good doctor’s adventurous and life-saving exploits across the vast northern territory.

In 1896 Dr. Joseph H. Romig traveled to Bethel, Alaska, and opened the first doctor’s office and hospital west of Sitka, at a time when there were very few non-native people living in remote southwest Alaska. Four decades later a book would be written about the good doctor’s adventurous and life-saving exploits across the vast northern territory.

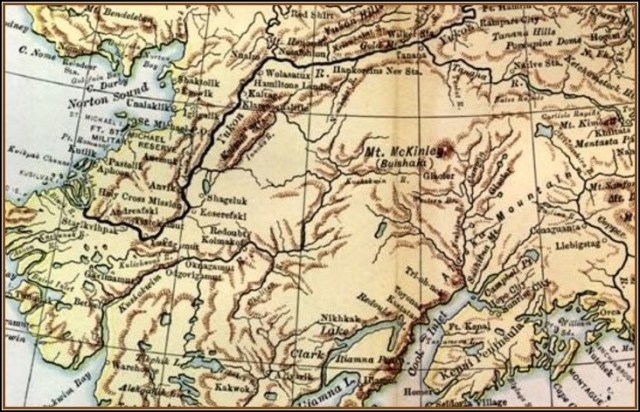

Joseph Herman Romig was born in Illinois in 1872. His parents were descendants of Moravian immigrants, and in exchange for his pledge to serve for seven years as a doctor at a mission, the Moravian Church sponsored his medical training. In 1896, Joseph married a nursing student he met at school, and the couple moved to Bethel to join Joseph’s older sister and her husband as missionaries to the Yup’ik people of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Bethel was barely a village at that time, consisting of only four houses, a chapel, an old Russian-style bath house and a small store. The Romig home was a simple two-room structure, and included the first hospital: one room with two homemade beds.

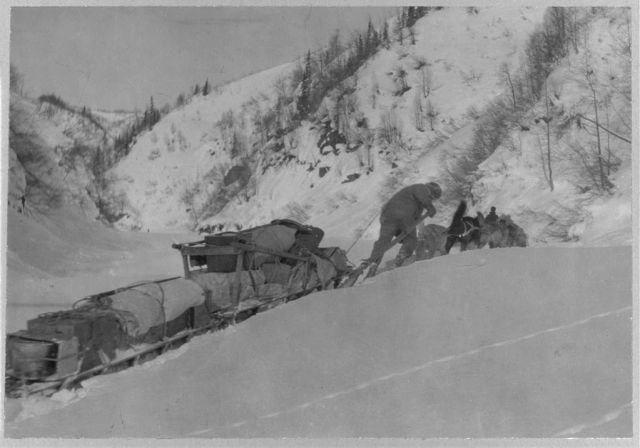

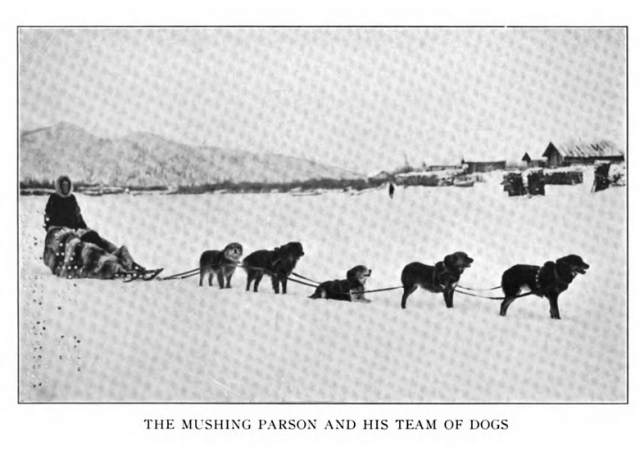

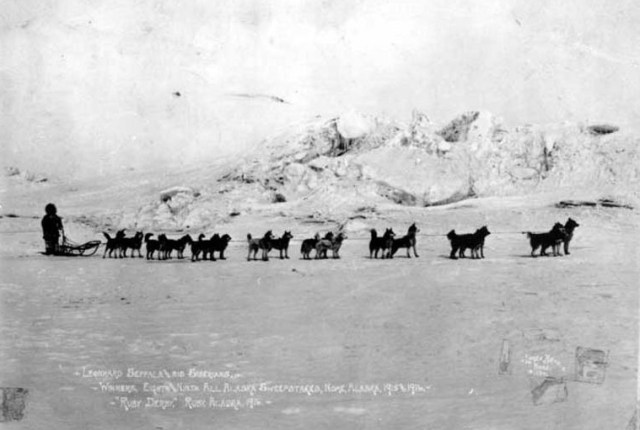

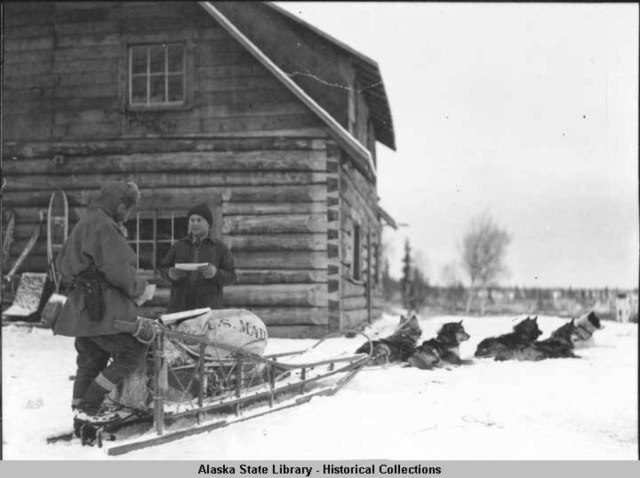

For a time, Dr. Romig was one of the only physicians in Alaska, and he became expert at dog mushing, as his practice stretched for hundreds of miles. He became known as the “dog team doctor” for traveling by dog sled throughout the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in the course of his work.

For a time, Dr. Romig was one of the only physicians in Alaska, and he became expert at dog mushing, as his practice stretched for hundreds of miles. He became known as the “dog team doctor” for traveling by dog sled throughout the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in the course of his work.

When his term of missionary service was complete Dr. Romig left Bethel, and in the following decades he played an eventful and important role in the growth of Alaska. In the 1920’s Dr. Romig set up a hospital in Nenana for the Alaska Railroad. In 1930, he was asked to head the Alaska Railroad Hospital in Anchorage. He would eventually be, in addition to a missionary and a doctor, a superintendent of schools, U.S. Commissioner, mayor of Anchorage (1937-38).

In 1939, Dr. Romig was appointed chief surgeon at Anchorage’s newly constructed state-of-the-art Providence Hospital, but he retired shortly thereafter, and purchased land on what would later be called Romig Hill. From his log cabin on the property, he started a “Board of Directors” club which eventually provided the founding members of the Anchorage Rotary Club. In the 1950’s and ’60’s Romig Ski Hill was a popular recreation area for Anchorage and provided a tow rope, lighted trails, a regulation jump, Quonset hut for warming up, and an intercom system which played polka music for the skiers.

In 1939, Dr. Romig was appointed chief surgeon at Anchorage’s newly constructed state-of-the-art Providence Hospital, but he retired shortly thereafter, and purchased land on what would later be called Romig Hill. From his log cabin on the property, he started a “Board of Directors” club which eventually provided the founding members of the Anchorage Rotary Club. In the 1950’s and ’60’s Romig Ski Hill was a popular recreation area for Anchorage and provided a tow rope, lighted trails, a regulation jump, Quonset hut for warming up, and an intercom system which played polka music for the skiers.

Joseph and Emily Romig moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado, where Joseph died in 1951. Although he was originally buried in Colorado, his remains were later disinterred and moved to Alaska to be buried in the family plot in Anchorage Memorial Park. J. H. Romig Junior High School, named in his honor for his dedication to youth and education and later renamed Romig Middle School, was built on Romig Hill in 1964.

Joseph and Emily Romig moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado, where Joseph died in 1951. Although he was originally buried in Colorado, his remains were later disinterred and moved to Alaska to be buried in the family plot in Anchorage Memorial Park. J. H. Romig Junior High School, named in his honor for his dedication to youth and education and later renamed Romig Middle School, was built on Romig Hill in 1964.

Dr. Romig’s life story and his adventures in southwest Alaska became the subject of a book, Dog-Team Doctor: The Story of Dr. Romig, by Eva Greenslit Anderson, published in 1940.

This story is excerpted from the new book Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, which will be published May 14, 2016; advance orders are available now. All advance ordered copies will be signed by the author, Helen Hegener; after May 14 books will be shipped directly from the publisher and will not be signed. Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, by Helen Hegener. $24.95 plus $5.00 shipping & handling. 320 pages, 6′ x 9″ b/w format, includes maps, charts, bibliography, indexed. Click this link to order.

This story is excerpted from the new book Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, which will be published May 14, 2016; advance orders are available now. All advance ordered copies will be signed by the author, Helen Hegener; after May 14 books will be shipped directly from the publisher and will not be signed. Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, by Helen Hegener. $24.95 plus $5.00 shipping & handling. 320 pages, 6′ x 9″ b/w format, includes maps, charts, bibliography, indexed. Click this link to order.

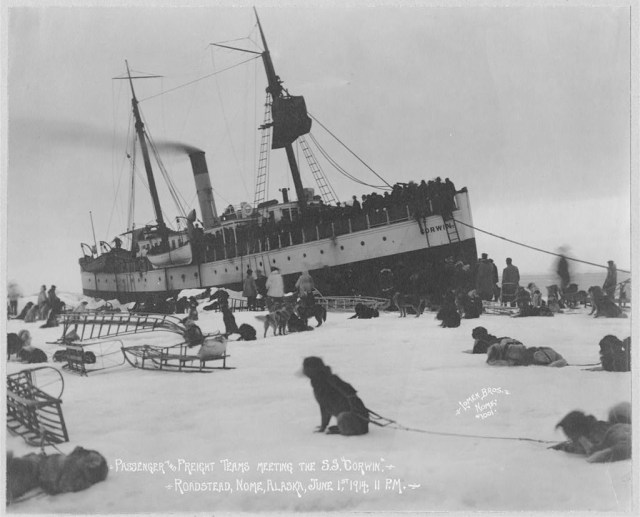

In 1910, a Scottish nobleman who lived in Nome, Fox Maule Ramsey, crossing the Bering Strait to Siberia and purchased 70 Siberian racing huskies. In that year’s All Alaska Sweepstakes race, a 408-mile run from Nome to Candle and return, Ramsay’s dogs won 1st, 2nd and 4th places, with the first place team driven John “Iron Man” Johnson with his peerless lead dog Kolyma setting the pace. Named for the great Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia, the striking black-and-white blue-eyed Siberian husky was Johnson’s favorite, and his constant companion.

In 1910, a Scottish nobleman who lived in Nome, Fox Maule Ramsey, crossing the Bering Strait to Siberia and purchased 70 Siberian racing huskies. In that year’s All Alaska Sweepstakes race, a 408-mile run from Nome to Candle and return, Ramsay’s dogs won 1st, 2nd and 4th places, with the first place team driven John “Iron Man” Johnson with his peerless lead dog Kolyma setting the pace. Named for the great Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia, the striking black-and-white blue-eyed Siberian husky was Johnson’s favorite, and his constant companion.

San Francisco, Cal., Jan. 9, 1915 – John Johnson, “The Iron Man of Alaska,” and his pack of $30,000 Siberian wolf dogs, winners of the All Alaska Sweepstakes race, have come down here to loaf a little while in the land of soft delights. With Johnson is Bill Brady, another celebrity of the “land that God forgot,” and his string of huskies, valued at $20,000.

San Francisco, Cal., Jan. 9, 1915 – John Johnson, “The Iron Man of Alaska,” and his pack of $30,000 Siberian wolf dogs, winners of the All Alaska Sweepstakes race, have come down here to loaf a little while in the land of soft delights. With Johnson is Bill Brady, another celebrity of the “land that God forgot,” and his string of huskies, valued at $20,000.

Lake Tahoe’s Winter Carnivals were much-anticipated and popular events in the early 1900’s, and while dog sledding and racing began during winter carnivals in the late 1890’s, the first and official sled dog race in the continental U.S. was reportedly held in Truckee, California, in 1915. Bert Cassidy, editor of the Truckee Republican (Sierra Sun), described the event: “Crowds of people had been arriving in Truckee on each train… all hotel accommodations had long since been taken… movie cameramen were legion… all the bigger papers had sent sports editors.”

Lake Tahoe’s Winter Carnivals were much-anticipated and popular events in the early 1900’s, and while dog sledding and racing began during winter carnivals in the late 1890’s, the first and official sled dog race in the continental U.S. was reportedly held in Truckee, California, in 1915. Bert Cassidy, editor of the Truckee Republican (Sierra Sun), described the event: “Crowds of people had been arriving in Truckee on each train… all hotel accommodations had long since been taken… movie cameramen were legion… all the bigger papers had sent sports editors.”

The newest book from Northern Light Media, Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, is in the final proofing stage before indexing the book, and I thought a peek between the covers might be fun for readers looking forward to this book. Here, then, are a few page shots from the layout in production (below).

The newest book from Northern Light Media, Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, is in the final proofing stage before indexing the book, and I thought a peek between the covers might be fun for readers looking forward to this book. Here, then, are a few page shots from the layout in production (below).

Alaskan Sled Dog Tales will be published May 14, 2016; advance orders are available now. All advance ordered copies will be signed by the author, Helen Hegener; after May 14 books will be shipped directly from the publisher and will not be signed. Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, by Helen Hegener. $24.95 plus $5.00 shipping & handling. 320 pages, 6′ x 9″ b/w format, includes maps, charts, bibliography, indexed.

Alaskan Sled Dog Tales will be published May 14, 2016; advance orders are available now. All advance ordered copies will be signed by the author, Helen Hegener; after May 14 books will be shipped directly from the publisher and will not be signed. Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, by Helen Hegener. $24.95 plus $5.00 shipping & handling. 320 pages, 6′ x 9″ b/w format, includes maps, charts, bibliography, indexed.  The history of Alaska was in large part written behind a team of sled dogs.

The history of Alaska was in large part written behind a team of sled dogs. Dozens of old photographs and postcards are included, along with the entire booklet published by Esther Birdsall Darling in 1916, titled The Great Dog Races of Nome, which details the first eight years of the All Alaska Sweepstakes race, from 1908 to 1916.

Dozens of old photographs and postcards are included, along with the entire booklet published by Esther Birdsall Darling in 1916, titled The Great Dog Races of Nome, which details the first eight years of the All Alaska Sweepstakes race, from 1908 to 1916. “Relying upon material written from the late 1890s through the early ‘30s, [Hegener] catalogues how sled dogs provided Alaskan residents the ability to traverse enormous distances, deliver critical supplies and maintain communication from within and outside Alaska. The episodes she recounts are stirring, filled with human and animal bravery. Some are simply mind-boggling, filling the reader with awe and enormous respect for dog and driver alike.” David Fox, in the

“Relying upon material written from the late 1890s through the early ‘30s, [Hegener] catalogues how sled dogs provided Alaskan residents the ability to traverse enormous distances, deliver critical supplies and maintain communication from within and outside Alaska. The episodes she recounts are stirring, filled with human and animal bravery. Some are simply mind-boggling, filling the reader with awe and enormous respect for dog and driver alike.” David Fox, in the  From the Wenatchee World, Wenatchee, Washington, June 29, 1909:

From the Wenatchee World, Wenatchee, Washington, June 29, 1909:

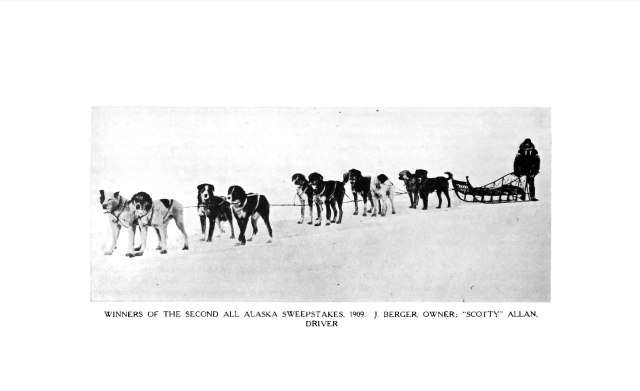

Greatest of all dog drivers in the world, winner of the classic All-Alaskan Sweepstakes dog race at Nome last April, A.A. Allan, “Scotty” Allan, as he is known to friends and all Alaskans, came down from Nome on the St. Croix to spend a well-earned vacation at the exposition. A wiry little Scotchman, standing five feet four and one-half inches is this “Scotty.” At 42 he is as spry as a high school boy, and every pound of the 150, which makes his weight, is filled with an energy which makes the whole a tireless machine.

Greatest of all dog drivers in the world, winner of the classic All-Alaskan Sweepstakes dog race at Nome last April, A.A. Allan, “Scotty” Allan, as he is known to friends and all Alaskans, came down from Nome on the St. Croix to spend a well-earned vacation at the exposition. A wiry little Scotchman, standing five feet four and one-half inches is this “Scotty.” At 42 he is as spry as a high school boy, and every pound of the 150, which makes his weight, is filled with an energy which makes the whole a tireless machine. By the time the two men reached the Butler Annex, where they are registered, Jake Berger found that while his two teams had won and he was $10,000 to the good, much of the money had been expended in purchasing and training dogs during the long winter and that he was just about even with the game. It mattered not, however, for he has a comfortable fortune, a paystreak which has not had the ends tapped as yet, and above all he is a true sportsman.

By the time the two men reached the Butler Annex, where they are registered, Jake Berger found that while his two teams had won and he was $10,000 to the good, much of the money had been expended in purchasing and training dogs during the long winter and that he was just about even with the game. It mattered not, however, for he has a comfortable fortune, a paystreak which has not had the ends tapped as yet, and above all he is a true sportsman. When Mr. Berger came out last fall he entrusted his dogs, a score in number, to “Scotty,” leaving a good sized bank account to see that they were properly trained. During the winter the latter tried all the dogs and with the purchase of a few selected animals entered Berger’s two teams. He also did something which was the surprise of everyone in Nome. All winter he kept using a big heavy basket sled in training his team. He was laughed at, but told all that he wanted a sled that would stand any kind of usage. About a half hour before the race he brought out a sled that has never had an equal in the north. Although twelve feet long it weighed but 31 pounds, and a feature of its construction was the use of every D violin string that could be purchased in Nome, which were used for lashing the joints. This spring there was a lack of music owing to this. His dog harness weighed nine ounces per dog, and his whole outfit of muklucks for himself and dogs, blankets for the animals and tugs and other equipment totaled, sleigh included, weighed only 42 pounds.

When Mr. Berger came out last fall he entrusted his dogs, a score in number, to “Scotty,” leaving a good sized bank account to see that they were properly trained. During the winter the latter tried all the dogs and with the purchase of a few selected animals entered Berger’s two teams. He also did something which was the surprise of everyone in Nome. All winter he kept using a big heavy basket sled in training his team. He was laughed at, but told all that he wanted a sled that would stand any kind of usage. About a half hour before the race he brought out a sled that has never had an equal in the north. Although twelve feet long it weighed but 31 pounds, and a feature of its construction was the use of every D violin string that could be purchased in Nome, which were used for lashing the joints. This spring there was a lack of music owing to this. His dog harness weighed nine ounces per dog, and his whole outfit of muklucks for himself and dogs, blankets for the animals and tugs and other equipment totaled, sleigh included, weighed only 42 pounds. Mr. Allan says that after years’ experience with dogs he decided that a cross between a setter and the native Alaskan dog proves the best traveler. Each animal for racing purposes should weigh between 70 and 90 pounds.

Mr. Allan says that after years’ experience with dogs he decided that a cross between a setter and the native Alaskan dog proves the best traveler. Each animal for racing purposes should weigh between 70 and 90 pounds. Excerpted from Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, by Helen Hegener, published in May, 2016 by Northern Light Media.

Excerpted from Alaskan Sled Dog Tales, by Helen Hegener, published in May, 2016 by Northern Light Media. As a writer I work with words on a daily basis, and I’ve been asked if it ever gets old, this spending my time at a keyboard instead of pursuing other potentially more exciting ways to make a living. Okay, I will admit there are times I envy my many photographer friends who travel to scenic places and bring back splendid photographs which not only make people oooh and ahhh but often bring the photographer a nice paycheck as well. I can take respectable photographs, but my forte is and always will be writing, because I love playing with words, selecting one over another to give a different meaning or inference, editing and rewriting until the meaning and intention flows smoothly and clearly. I believe the old adage, ‘The pen is mightier than the sword,’ because the world has been built on words, and they truly have power and magic.

As a writer I work with words on a daily basis, and I’ve been asked if it ever gets old, this spending my time at a keyboard instead of pursuing other potentially more exciting ways to make a living. Okay, I will admit there are times I envy my many photographer friends who travel to scenic places and bring back splendid photographs which not only make people oooh and ahhh but often bring the photographer a nice paycheck as well. I can take respectable photographs, but my forte is and always will be writing, because I love playing with words, selecting one over another to give a different meaning or inference, editing and rewriting until the meaning and intention flows smoothly and clearly. I believe the old adage, ‘The pen is mightier than the sword,’ because the world has been built on words, and they truly have power and magic. I’ve done a lot of writing this winter, in part because winter is a time conducive to writing, and in part because as one who makes a living with her computer I need to keep the paychecks coming in through whatever means and channels are available. And of course I love seeing my name in lights – I mean print – and even more I love sharing the fascinating history and wonderful stories of our great state’s colorful past. I’m pleased to say I have articles in three Alaskan magazines this month, all three favorites which I love reading and sharing with others:

I’ve done a lot of writing this winter, in part because winter is a time conducive to writing, and in part because as one who makes a living with her computer I need to keep the paychecks coming in through whatever means and channels are available. And of course I love seeing my name in lights – I mean print – and even more I love sharing the fascinating history and wonderful stories of our great state’s colorful past. I’m pleased to say I have articles in three Alaskan magazines this month, all three favorites which I love reading and sharing with others:  I’ve also been writing presentations: In February I gave another talk and slideshow to the Palmer Historical Society on the old Alaskan roadhouses, and this month I’m once again speaking and presenting a slideshow at the venerable Talkeetna Roadhouse at their Iditarod Sunday dinner, about – what else? – sled dogs and roadhouses! I’ve always said I’m not much of a speaker, which is fairly common for writers, but I do enjoy sharing the history of Alaska in this very different and interactive format, and it’s always a fun time to meet old and new friends!

I’ve also been writing presentations: In February I gave another talk and slideshow to the Palmer Historical Society on the old Alaskan roadhouses, and this month I’m once again speaking and presenting a slideshow at the venerable Talkeetna Roadhouse at their Iditarod Sunday dinner, about – what else? – sled dogs and roadhouses! I’ve always said I’m not much of a speaker, which is fairly common for writers, but I do enjoy sharing the history of Alaska in this very different and interactive format, and it’s always a fun time to meet old and new friends! “On January 28, 1925, newspapers and radio stations broke a terrifying story — diphtheria had broken out in Nome, Alaska, separated from the rest of the world for seven months by a frozen ocean. With aviation still in its infancy and one of the harshest winters on record, only ancient means — dogsled — could save the town. In minus 60 degrees, over 20 men and at least 150 dogs, among them the famous Balto, set out to relay the antitoxin across 674 miles of Alaskan wilderness to save the town. An ageless adventure that has captured the imagination of children and adults throughout the world for almost a century, the story has become known as the greatest dog story ever told.”

“On January 28, 1925, newspapers and radio stations broke a terrifying story — diphtheria had broken out in Nome, Alaska, separated from the rest of the world for seven months by a frozen ocean. With aviation still in its infancy and one of the harshest winters on record, only ancient means — dogsled — could save the town. In minus 60 degrees, over 20 men and at least 150 dogs, among them the famous Balto, set out to relay the antitoxin across 674 miles of Alaskan wilderness to save the town. An ageless adventure that has captured the imagination of children and adults throughout the world for almost a century, the story has become known as the greatest dog story ever told.” The description above is for the documentary film Icebound, which premiered in Anchorage in December, 2013. The film was described in an

The description above is for the documentary film Icebound, which premiered in Anchorage in December, 2013. The film was described in an

Under Race Marshall Sue Allen’s experienced guidance the start went off smoothly, with many handlers later commenting that it was a well-planned and executed beginning to the race for the 33 teams, a large percentage of them seeking to qualify for the 1,000-mile Iditarod and Yukon Quest races. The race checkpoints from the start at Happy Trails Kennel in Big Lake included Yentna Station at 56.1 miles out, the Finger Lake checkpoint at 129.9 miles, the Talvista checkpoint at 166.6 miles, and Yentna Station again at 213.9 miles. The trail was reported to be in good condition, which was later confirmed by many of the mushers.

Under Race Marshall Sue Allen’s experienced guidance the start went off smoothly, with many handlers later commenting that it was a well-planned and executed beginning to the race for the 33 teams, a large percentage of them seeking to qualify for the 1,000-mile Iditarod and Yukon Quest races. The race checkpoints from the start at Happy Trails Kennel in Big Lake included Yentna Station at 56.1 miles out, the Finger Lake checkpoint at 129.9 miles, the Talvista checkpoint at 166.6 miles, and Yentna Station again at 213.9 miles. The trail was reported to be in good condition, which was later confirmed by many of the mushers. The first evening each musher’s start differential was added to a mandatory six-hour layover at the Yentna Station checkpoint, and just before midnight the first musher was back on the trail again: Ryan Redington driving 13 dogs at a fast 9.5 miles per hour after dropping one of the 14 he’d started with. Rick Casillo and Sebastien Vergnaud were close behind Redington. By 1 am over half the teams were out of Yentna and on their way to the Skwentna Hospitality Stop, and by 4 am all of the teams were back on the trail again.

The first evening each musher’s start differential was added to a mandatory six-hour layover at the Yentna Station checkpoint, and just before midnight the first musher was back on the trail again: Ryan Redington driving 13 dogs at a fast 9.5 miles per hour after dropping one of the 14 he’d started with. Rick Casillo and Sebastien Vergnaud were close behind Redington. By 1 am over half the teams were out of Yentna and on their way to the Skwentna Hospitality Stop, and by 4 am all of the teams were back on the trail again. At 7:31 Saturday morning front-runner Ryan Redington pulled into the halfway point at Finger Lake. Rick Casillo followed at 7:41, Charley Bejna at 7:44, and Sebastian Vergnaud at 7:45. At 8:30 I posted a good morning on Facebook and asked where everyone was watching the race from. Responses ranged across the globe, with fans commenting from many different states and as far away as Norway, Germany, The Netherlands, England, New Zealand, the

At 7:31 Saturday morning front-runner Ryan Redington pulled into the halfway point at Finger Lake. Rick Casillo followed at 7:41, Charley Bejna at 7:44, and Sebastian Vergnaud at 7:45. At 8:30 I posted a good morning on Facebook and asked where everyone was watching the race from. Responses ranged across the globe, with fans commenting from many different states and as far away as Norway, Germany, The Netherlands, England, New Zealand, the  Ryan Redington led the pack out of Finger Lake at 10:51 am Saturday morning, nearly an hour ahead of the second-place musher, Rick Casillo. Limited communications with the remote Finger Lake checkpoint were made worse by a snowstorm moving in, making it tricky at best to get updates on the mushers’ times and team counts, but mushers continued to arrive and depart from the checkpoint throughout the day. During the second day of the race the news media carried many reports of Nicolai’s accident, including a

Ryan Redington led the pack out of Finger Lake at 10:51 am Saturday morning, nearly an hour ahead of the second-place musher, Rick Casillo. Limited communications with the remote Finger Lake checkpoint were made worse by a snowstorm moving in, making it tricky at best to get updates on the mushers’ times and team counts, but mushers continued to arrive and depart from the checkpoint throughout the day. During the second day of the race the news media carried many reports of Nicolai’s accident, including a

At 12:30 am race volunteer Josh Klauder posted on Facebook that the three front-running teams were eligible to leave Yentna, Ryan Redington and Rick Casillo both at 3:49 AM, and Sebastien Vergnaud at 4:09 AM. It was going to be a fast race down the home stretch!

At 12:30 am race volunteer Josh Klauder posted on Facebook that the three front-running teams were eligible to leave Yentna, Ryan Redington and Rick Casillo both at 3:49 AM, and Sebastien Vergnaud at 4:09 AM. It was going to be a fast race down the home stretch!