“In the summer of 1879 I was stationed at Fort Wrangell in southeastern Alaska, whence I had come the year before, a green young student fresh from college and seminary–very green and very fresh–to do what I could towards establishing the white man’s civilization among the Thlinget Indians. I had very many things to learn and many more to unlearn.” These are the opening words of Reverend Samuel Hall Young’s classic 1915 book, Alaska Days with John Muir (Fleming H. Revell Co., New York 1915). Young paints a vivid picture of the iconic naturalist, arriving on a steamboat with a group of people Young had come down to the dock to meet: “Standing a little apart from them as the steamboat drew to the dock, his peering blue eyes already eagerly scanning the islands and mountains, was a lean, sinewy man of forty, with waving, reddish-brown hair and beard, and shoulders slightly stooped. He wore a Scotch cap and a long, gray tweed ulster, which I have always since associated with him, and which seemed the same garment, unsoiled and unchanged, that he wore later on his northern trips. He was introduced as Professor Muir, the Naturalist.”

“In the summer of 1879 I was stationed at Fort Wrangell in southeastern Alaska, whence I had come the year before, a green young student fresh from college and seminary–very green and very fresh–to do what I could towards establishing the white man’s civilization among the Thlinget Indians. I had very many things to learn and many more to unlearn.” These are the opening words of Reverend Samuel Hall Young’s classic 1915 book, Alaska Days with John Muir (Fleming H. Revell Co., New York 1915). Young paints a vivid picture of the iconic naturalist, arriving on a steamboat with a group of people Young had come down to the dock to meet: “Standing a little apart from them as the steamboat drew to the dock, his peering blue eyes already eagerly scanning the islands and mountains, was a lean, sinewy man of forty, with waving, reddish-brown hair and beard, and shoulders slightly stooped. He wore a Scotch cap and a long, gray tweed ulster, which I have always since associated with him, and which seemed the same garment, unsoiled and unchanged, that he wore later on his northern trips. He was introduced as Professor Muir, the Naturalist.”

S. Hall Young, circa 1879

Reverend Young and Mr. Muir were destined to become great friends, and Young details their first mountain-climbing jaunt with great relish: “I had been with mountain climbers before, but never one like him. A deer-lope over the smoother slopes, a sure instinct for the easiest way into a rocky fortress, an instant and unerring attack, a serpent-glide up the steep; eye, hand and foot all connected dynamically; with no appearance of weight to his body—as though he had Stockton’s negative gravity machine strapped on his back.” The book is online to read or download free. The first two chapters are a breathless recitation of the thrilling climb across a glacier and up a sheer mountainside to see the sunset from the peak, and when near-tragedy befalls Reverend Young the story relates Muir’s almost unbelievably heroic rescue of his friend.

Reverend Young, the first missionary in Alaska, recounts a six-week voyage through southeastern waters he undertook in a great cedar canoe with Muir and a half-dozen Thlinget Indians as scouts and crew. Visiting villages along the route, Young noted: “I took the census of each village, getting the heads of the families to count their relatives with the aid of beans,—the large brown beans representing men, the large white ones, women, and the small Boston beans, children. In this manner the first census of southeastern Alaska was taken.”

Reverend Young, the first missionary in Alaska, recounts a six-week voyage through southeastern waters he undertook in a great cedar canoe with Muir and a half-dozen Thlinget Indians as scouts and crew. Visiting villages along the route, Young noted: “I took the census of each village, getting the heads of the families to count their relatives with the aid of beans,—the large brown beans representing men, the large white ones, women, and the small Boston beans, children. In this manner the first census of southeastern Alaska was taken.”

John Muir circa 1875

One night John Muir stumbled into their Glacier Bay camp with two Indians who’d guided the great explorer off the glacier which would bear his name. Muir had been long overdue when Reverend Young sent them to build a beacon fire, which Muir admitted turned his back in the right direction, but then he excitedly added, “Man, man; you ought to have been with me. You’ll never make up what you have lost to-day. I’ve been wandering through a thousand rooms of God’s crystal temple. I’ve been a thousand feet down in the crevasses, with matchless domes and sculptured figures and carved ice-work all about me. Solomon’s marble and ivory palaces were nothing to it. Such purity, such color, such delicate beauty! I was tempted to stay there and feast my soul, and softly freeze, until I would become part of the glacier. What a great death that would be!”

Glacier, Stickeen Valley

At the end of the voyage Reverend Young wrote, “I have made many voyages in that great Alexandrian Archipelago since, traveling by canoe over fifteen thousand miles—not one of them a dull one—through its intricate passages; but none compared, in the number and intensity of its thrills, in the variety and excitement of its incidents and in its lasting impressions of beauty and grandeur, with this first voyage when we groped our way northward with only Vancouver’s old chart as our guide.”

Stickeen

The following spring John Muir returned from his home in the sunny south, determined to visit the glaciers they had not seen on their trip the previous fall, and they once more set out in a cedar canoe with Native guides. Reverend Young wrote: “When we were about to embark I suddenly thought of my little dog Stickeen and made the resolve to take him along. My wife and Muir both protested and I almost yielded to their persuasion. I shudder now to think what the world would have lost had their arguments prevailed! That little, long-haired, brisk, beautiful, but very independent dog, in co-ordination with Muir’s genius, was to give to the world one of its greatest dog-classics.”

Stickeen: John Muir and the Brave Little Dog, by John Muir, as retold by Donnell Rubay. Scholastic Inc., 1998, 30 pages. Illustrated in color by Christopher Canyon.

The book which Muir would later write was, of course, the classic Stickeen: The Story of a Dog (Riverside Press,Cambridge, MA 1909), which relates one of John Muir’s most harrowing adventures, accompanied only by his friend’s small dog. Unable to convince the adventure-loving dog to remain behind, Muir set out to explore the face of a great glacier, and reached a dangerous crevasse blocking his way, with only a thin ice-bridge as a crossing and unimaginable black depths below it. He wrote of little Stickeen, showing something of his own nature in telling the story: “Never before had the daring midget seemed to know that ice was slippery or that there was any such thing as danger anywhere. His looks and tones of voice when he began to complain and speak his fears were so human that I unconsciously talked to him as I would to a frightened boy, and in trying to calm his fears perhaps in some measure moderated my own. ‘Hush your fears, my boy,’ I said, ‘we will get across safe, although it is not going to be easy. No right way is easy in this rough world. We must risk our lives to save them. At the worst we can only slip, and then how grand a grave we will have, and by and by our nice bones will do good in the terminal moraine.'”

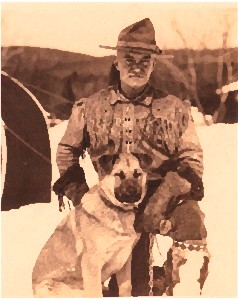

“The Mushing Parson” frontispiece of his autobiography, Hall Young of Alaska, An Autobiography

Reverend Young and John Muir remained lifelong friends. During the 10 years he lived and worked in Wrangell with his family, Rev. Young established several southeastern missions and became a man of some standing. In 1897 he was strongly considered for appointment as governor of the territory of Alaska by President McKinley. Instead he traveled over Chilkoot Pass and down the Yukon River at the height of the Klondike gold rush, and established the first Presbyterian church in Dawson City in 1898. Traveling down the Yukon River over the next three years, he organized missions at Eagle, Rampart, Nome, and Teller. In 1901 he was appointed superintendent of all Alaska Presbyterian missions. He lived at Skagway in 1902-1903, at Council in 1903-1904, at Fairbanks from 1904-06 and again 1907-08, at Teller in 1907, at Cordova in 1908-10, and Iditarod in 1911-12. During those years he gained a ‘Doctor of Divinity’ designation and became known as “the mushing parson” because of his many long journeys by dogteam.

In 1913 Dr. Young wrote an article for the church publication The Continent in which he shared his story of a journey via dogteam from Iditarod to Seward over the Iditarod Trail, and then by steamer to Cordova, for an important General Assembly of the church. He was accompanied by a young Scotchman and experienced dog musher named Breeze, and his colorful first-hand descriptions of the trail are a delight to read, the few photographs accompanying the article are to treasure. “The journey is to lead across three high ranges of mountains and two great valleys, the Kuskokwim and the Susitna. The trail has been but recently laid out by the government and is little used, but there are roadhouses here and there at irregular intervals and we will take enough provisions with us for emergencies. As to its being at all a formidable undertaking, why, the prospectors, miners and hunters of Alaska take far harder and longer trips constantly and break the trail for their dogs the whole way in unexplored territory. I anticipate the pleasure of that trip across new country with keen delight.”

In 1913 Dr. Young wrote an article for the church publication The Continent in which he shared his story of a journey via dogteam from Iditarod to Seward over the Iditarod Trail, and then by steamer to Cordova, for an important General Assembly of the church. He was accompanied by a young Scotchman and experienced dog musher named Breeze, and his colorful first-hand descriptions of the trail are a delight to read, the few photographs accompanying the article are to treasure. “The journey is to lead across three high ranges of mountains and two great valleys, the Kuskokwim and the Susitna. The trail has been but recently laid out by the government and is little used, but there are roadhouses here and there at irregular intervals and we will take enough provisions with us for emergencies. As to its being at all a formidable undertaking, why, the prospectors, miners and hunters of Alaska take far harder and longer trips constantly and break the trail for their dogs the whole way in unexplored territory. I anticipate the pleasure of that trip across new country with keen delight.”

Dr. Young ready for the winter trail.

Dr. Young regaled his readers with wonderful descriptions of the trail. Upon arriving at Knik he hopes to board a boat and cross the wide Cook’s Inlet to Sunrise, on the northern end of the Kenai Peninsula, but the boat doesn’t come before Rev. Young determines that he must continue in order to arrive in time for the meeting. “The worst mountain pass of all is before us–Crow Creek Pass over the high Alaska range. Fearsome tales are told me of this pass, but there is nothing to do but to try it. Breeze leaves me here and I hire a young prospector, Fred Taulman, to take me to Seward. Were it not for my lame back I would go alone, but they all say that the pass is too dangerous to be traveled singly even by a strong and vigorous person. So on March 21 we hitched up our eager dogs, whose three days rest has put them in high spirits, and hit the trail again around the head of Knik Arm.

Old Knik Roadhouse circa 1914

“Over dangerous ice, sometimes through the salt water that covers it, with now and then a stretch of good trail, we come to Old Knik. It is only a seventeen mile stretch, but my back is so bad that when I arrive at the roadhouse I am in convulsions of pain. A hot drink and hot applications soothe me, but there is little sleep for me that night.

Summit of Crow Creek Pass

“Now hard climbing up a steep road to the base of the pass at Raven Creek roadhouse. A storm is blowing. The snow banners on the mountains that overlook the pass and the fast falling snow make it impossible for us to go on, so we spend a day at this fine roadhouse, kept by three men who are hunters, prospectors and hotel keepers as occasion requires. The second day they hitch up four big dogs as big as Shetland ponies to supplement our smaller ones, and a sturdy mountaineer with ‘creepers’ on his feet comes to pilot us over the summit. From daylight until noon we struggle before reaching the summit, making only five miles in six hours. The descent from the summit is almost sheer for 2,000 feet.”

The Mushing Parson and his team

The good reverend had many such adventures over the years, and he shared them in numerous articles and books, including his landmark autobiography, Hall Young of Alaska, “The Mushing Parson.” In 1991 a reference librarian at the public library in Anchorage tracked down a lengthy letter from John Muir to his friend S. Hall Young, dated March 31, 1910, in which the respected naturalist shared his opinion of the title of the book: “I feel pretty sure that you should change the name of the book which you say you will call the ‘Mushing Parson.’ ‘Mushing’ is slang, even in Alaska, and parsons should be better described no matter how they travel. I am sure that it would be a very bad title. Nothing of that catchy character should ever be attached to a sound hard work of real literature.”

The librarian, Bruce Merrell, noted, “S. Hall Young bristled at Muir’s suggestion that he abandon the term ‘mushing person.’ ‘…I have consulted my most literary Alaska friends and some in the East,’ he wrote Muir in his next letter, ‘and all are taken with the title…In fact, there is no other word used up here to express the same idea.'”

Dr. S. Hall Young, 1914

The remaining years of Rev. Young’s life were detailed in a biography by Alaskan historian Robert DeArmond: “From 1913 until 1921, Young held the title Special Representative of the Presbyterian National Board of Missions, with headquarters in New York, and during that time he made many trips back to Alaska. His wife, Fannie Kellogg Young died in 1915. He was named general missionary for Alaska in 1922 and superintendent of Alaska missions in 1924, with headquarters in Seattle. In the summer of 1927, as he approached his 80th birthday, he escorted three different groups of Presbyterians to Alaska; then went east to attend a reunion. He was riding in a friend’s car when it had a flat tire. When Young stepped out, he was struck by an inter-urban trolley. He died in the Clarksburg, West Virginia, Hospital September 2, 1927, and was buried beside Mrs. Young at Syracuse, New York. His books include The Klondike Clan, Adventures in Alaska, and an autobiography, Hall Young of Alaska, published shortly after his death. It dwells particularly upon his first decade in Alaska and his work with the Natives. Mount Young in the Chilkat Range, Young Island in Glacier Bay, and Young Rock, which he discovered near Wrangell, were all named for S. Hall Young.”

For more information:

• S. Hall Young: The Sierra Club John Muir Exhibit

• An Alaskan “Mush” to Presbytery

• A Letter from John Muir to S. Hall Young, May 31, 1910

• Hall Young of Alaska, An Autobiography

• Alaska Days with John Muir

• S. Hall Young at Wikipedia

Share this page with your friends through social media:

Over the past couple of weeks I’ve been watching with interest as reporters from KTUU Channel 2 in Anchorage have been visiting old roadhouses around the state for their program Road Trippin’ Alaska. They’ve already visited several of the classic roadhouses I’d earmarked for inclusion in my upcoming book about the roadhouses, such as the Talkeetna Roadhouse, the Chatanika Roadhouse, the Black Rapids Roadhouse, and the Gakona Roadhouse. These great roadhouses have also been featured by artist and author Ray Bonnell in Alaska Sketchbook and his column for the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

Over the past couple of weeks I’ve been watching with interest as reporters from KTUU Channel 2 in Anchorage have been visiting old roadhouses around the state for their program Road Trippin’ Alaska. They’ve already visited several of the classic roadhouses I’d earmarked for inclusion in my upcoming book about the roadhouses, such as the Talkeetna Roadhouse, the Chatanika Roadhouse, the Black Rapids Roadhouse, and the Gakona Roadhouse. These great roadhouses have also been featured by artist and author Ray Bonnell in Alaska Sketchbook and his column for the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. The short video visits are fun and informative, and many of the roadhouses have been filmed more than once. For example, at the Talkeetna Roadhouse there’s an overview of the history of Talkeetna and the roadhouse, and in other videos the reporters join roadhouse owner Trisha Costello to learn pie-making, visit the local radio station and check out the recycling center.

The short video visits are fun and informative, and many of the roadhouses have been filmed more than once. For example, at the Talkeetna Roadhouse there’s an overview of the history of Talkeetna and the roadhouse, and in other videos the reporters join roadhouse owner Trisha Costello to learn pie-making, visit the local radio station and check out the recycling center. An Instagram feed and additional photos showcase more history and details about the roadhouses, and there’s a Road Trippin’ ‘I Spy‘ game to play in conjunction with the program. Check out KTUU’s Morning Edition for the next roadhouse on their statewide tour!

An Instagram feed and additional photos showcase more history and details about the roadhouses, and there’s a Road Trippin’ ‘I Spy‘ game to play in conjunction with the program. Check out KTUU’s Morning Edition for the next roadhouse on their statewide tour!