On the editorial pages of the May-June, 2019 issue of Alaskan History Magazine there is a small photo of an Alaskan legend whose spirit inspired the publication of the magazine. Nellie Neal Lawing, known as Alaska Nellie by generations of Alaskans, left a legacy of courage, service to others, and dauntless resilience which the publisher of Alaskan History Magazine aspires to with each issue. The following article, written by Alaskan author and publisher of the magazine, Helen Hegener, first appeared in Alaska Dispatch several years ago.

On the editorial pages of the May-June, 2019 issue of Alaskan History Magazine there is a small photo of an Alaskan legend whose spirit inspired the publication of the magazine. Nellie Neal Lawing, known as Alaska Nellie by generations of Alaskans, left a legacy of courage, service to others, and dauntless resilience which the publisher of Alaskan History Magazine aspires to with each issue. The following article, written by Alaskan author and publisher of the magazine, Helen Hegener, first appeared in Alaska Dispatch several years ago.

“There were possibilities of an extensive business at this place for at least three years, as I saw it, and now I would be needing a dog team and dog kennels, a place for harnesses and a small building in which to cook dog food. On the mountain above the lodge I cut logs for the kennels and the cookhouse.” ~Nellie Neal Lawing in her autobiography, Alaska Nellie

Nellie Trosper Neal Lawing, familiar to Alaskans as “Alaska Nellie,” lived a life much larger than most, even by Alaskan standards. She was a fisherman, a hunter, a trapper, a cook and a roadhouse keeper; she fed the crews building the Alaska Railroad, welcomed princes and presidents into her home, guided big game hunters and developed an impressive trophy collection of her own. She mushed a dog team, kept a pet bear cub, became famous for her strawberry pies, and saw a movie made about her adventures. She was one of a kind, an Alaskan original, and she lived life to the fullest.

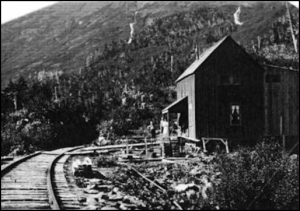

Grandview Roadhouse, Alaska Railroad mile 44.9, 1915

Nellie arrived in Seward on July 3, 1915, just as construction of the Alaska Railroad was getting underway. She wrote in her autobiography, Alaska Nellie, that she set out to seek a contract “to run the eating houses on the southern end of the Alaska Railroad,” and she described her effort: “On my first time out on an Alaskan trail, I had walked one hundred fifty miles and as usual was alone. This accomplishment, in itself, might have satisfied some, but I was out here in this great new country to contribute something to others, and I felt this means could best be served by becoming the ‘Fred Harvey’ of the government railroad in Alaska.”

Nellie’s early life is succinctly described in an article written by Lezlie Murray, Visitor Services Director, Chugach National Forest, and published in Fall 2011 issue of SourDough Notes:

“The oldest of 12 children, Nellie Trosper was born into a farm family in Saint Joseph, Mo., where she dreamed of coming to Alaska. As a young child she learned to trap and hunt in the countryside around her parent’s farm, becoming a good shot and capable woods woman. She left home in her late twenties after she had helped to raise her brothers and sisters and could be spared. A diminutive woman barely five feet tall, Nellie began to work her way to Alaska in 1901, stair-stepping her way through the west. She spent the most time in Cripple Creek, Colorado, where she worked at a variety of jobs, owned her own hotel and married a prominent assayer. Unhappy in her marriage due to abuse at home, she made the decision to divorce and moved on to California, where she booked steerage to Seward, Alaska.”

Nellie Neal with a mannequin on porch of the Grandview Roadhouse, 1915

Likely due in part to her plucky approach, she was awarded a lucrative government contract to run a roadhouse at mile 44.9, a scenic location she promptly named Grandview. Her agreement with the Alaska Engineering Commission was to provide food and lodging for the government employees; her skill with a rifle filled out the menu, and her gifted storytelling kept her guests highly entertained. Nellie described the accommodations at Grandview in her book, ‘Alaska Nellie’:

“The house was small but comfortable. A large room with thirteen bunks, used as sleeping quarters for the men, was just above the dining room. A small room above the kitchen served as my quarters. To the rear of the building a stream of clear, cold water flowed down from the mountain and was piped into the kitchen. Nature was surely in a lavish mood when she created the beauty of the surroundings of this place. The timber-clad mountains, the flower-dotted valley, the irresistible charm of the continuous stretches of mountains and valleys was something in which to revel.”

Nellie in her later years, with her treasured gold nugget necklace

Wiry and independent, Nellie was an excellent shot and a respected big game guide, and she rapidly accumulated an impressive array of wildlife trophies. She maintained a dog team in winter, and trapped along the corridor which would later become the Seward Highway. Once during a blizzard the local contract mail carrier, Henry Collman, didn’t arrive when he was expected, so Nellie hitched up her dog team and set out to find him. She located the mail carrier badly frozen in an area which had claimed several lives. Nellie took the young man back to her roadhouse to warm up, and then set off to finish delivering his mail sacks and pouches, which she later learned contained valuable goods, to the waiting train. For her courageous efforts the town of Seward declared her a hero and awarded her a gold nugget necklace, with a diamond set in its large pendant nugget. Nellie treasured her necklace to the end of her days.

Nellie Neal

Nellie tells another dog team story in her book: “One cold winter day in December when the daylight was only a matter of minutes and the lamps were burning low, two U.S. marshals, Marshals Cavanaugh and Irwin, together with Jack Haley and Bob Griffiths, arrived at the roadhouse.

“The heavy wooden boxes they were removing from their sleds had been brought from the Iditarod mining district. They contained $750,000 in gold bullion.

“‘Where do you want to put this, Nellie?’ called the men, carrying their precious burden.

“‘Right here under the dining room table is as good a place as any,’ I answered.

And it was as simple as that. There it stayed until the men carried it back to the sleds, next day. They were able to go to sleep, for it was as safe right there in my dining room as it would have been in the United States Mint. No one would dare to touch it.”

Nellie and her trophies in front of the Dead Horse Road House

As work on the government railroad progressed, Nellie moved north and operated a roadhouse near the Susitna River, at a railroad camp known as Dead Horse. Because Dead Horse Hill was such a key location in the construction of the Alaska Railroad, a large roadhouse was built at the site in 1917 to accommodate the construction workers, officials, and occasional visitors. Management of the new roadhouse was given to the intrepid roadhouse keeper who had proven herself at Grandview.

Nellie took on running the Dead Horse Roadhouse with all the pluck and dedication she’d shown at Grandview, cooking meals on two large ranges for the dining room which seated 125 hungry workers at a time, and filling 60 lunch-buckets each night for the construction crews to take on their jobs the following day. In her autobiography she wrote, “I dished out as many as 12,000 to 14,000 meals per month, having two cooks, two waitresses and several yard men as help.”

In his book about the era and the area, Lavish Silence, Kenneth Marsh described the roadhouse accommodations: “…spring-less wooden bunks, straw mattresses and oil- drum wood-burning stove, all in one large room at the top of a flight of rickety stairs, held together by a warped wooden shell (which, at times, put up an uneven fight against the elements).”

In July, 1923, President Harding, his wife, and Secretary of State Herbert Hoover stayed at the Dead Horse Roadhouse on their way to the Golden Spike-driving ceremony at Nenana. The next morning Nellie served heaping plates of sourdough pancakes in her warm kitchen, commenting, “Presidents of the United States like to be comfortable when they eat, just like anyone else!”

In July, 1923, President Harding, his wife, and Secretary of State Herbert Hoover stayed at the Dead Horse Roadhouse on their way to the Golden Spike-driving ceremony at Nenana. The next morning Nellie served heaping plates of sourdough pancakes in her warm kitchen, commenting, “Presidents of the United States like to be comfortable when they eat, just like anyone else!”

“Before the Curry Hotel was built, Curry featured a famous old building called the Dead Horse Roadhouse. The proprietor was the famous Alaska Nellie, who was known for her incredible cooking abilities and extraordinary hunting skills. It is said she killed the largest grizzly bear ever seen at that time.” ~Steve Mahay, in The Legend of River Mahay

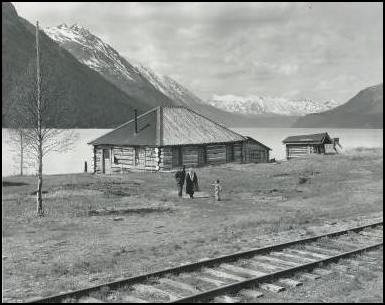

Nellie’s last home, on Kenai Lake

Finally in 1923, Nellie used her life’s savings to purchase her final home, a roadhouse on Kenai Lake. The railroad stop along the blue-green waters was renamed Lawing when Nellie Neal married Bill Lawing, and together they built the roadhouse into a popular tourist stop on the Alaska Railroad. Vegetables from Nellie’s garden were served with fresh fish from the lake or with game from the nearby hills, and Nellie’s stories, often embellished with her rollicking tall tales, kept her audiences delighted. Celebrities, politicians, tourists and even locals came to enjoy the purely Alaskan hospitality at the Lawings’ roadhouse on Kenai Lake.

Alaska Nellie became known far and wide, and the foreword to a 2010 reprinting of her autobiographical book, “Alaska Nellie,” by Patricia A. Heim, sums up her legendary status:

Alaska Nellie became known far and wide, and the foreword to a 2010 reprinting of her autobiographical book, “Alaska Nellie,” by Patricia A. Heim, sums up her legendary status:

“Nellie Neal Lawing was one of Alaska’s most charismatic, admired and famous pioneers. She was the first woman ever hired by the U.S. Government in Alaska in 1916. She was contracted to feed the hungry crews on the long awaited Alaska railroad connecting Seward to Anchorage. The conditions were harsh and supplies were limited. She delivered many of her meals by dogsled, fighting off moose attacks and hazards of the trail, often during below-zero blizzards. She always brought with her a great tale to tell of her adventures along the trail, how she had wrestled grizzlies, fought off wolves and moose, and caught the worlds largest salmon for their dinner, always in the old sourdough tradition. The workers listened and laughed with every bite.

“Nellie was an excellent cook, big game hunter, river guide, trail blazer, gold miner, and a great story-teller! It wasn’t long before Nellie became legendary and was known far and wide as the female ‘Davy Crockett’ of Alaska, her wilderness adventures and stories of survival on the trail spread like wildfire. Letters addressed simply ‘Nellie, Alaska’ were always delivered.

Nellie at her Kenai Lake cabin

“Nellie finally established herself at “Lawing, Alaska” on Kenai Lake, and converted an old roadhouse into a museum for her multitude of big game trophies. It was a great railroad stop and the highlight of any Alaskan visit. Her guest register of over 15,000 read like the Who’s Who of the early twentieth century: two U.S. Presidents, the Prince of Bulgaria, Will Rogers, authors, generals and many silent-screen movie stars.

“Nellie would entertain them all. Colt pistol on her hip and a baby black bear by her side, Nellie was always ready with one of her outrageous tales of adventure. ‘I was just minding my own business on Kenai Lake when a huge grizzly showed up, I fired my Colt, but as luck would have it, somehow, it misfired, I then had to kick the heck out of the brute and he ran off, but before he ran off he bit me good, right on the wrist, see here.’ She would then fold back her sleeve to show a scarred arm.

“Nellie was so popular and loved that she was honored with an “Alaska Nellie Day” on January 21, 1956.”

Bill and Nellie Lawing at their cabin beside Kenai Lake.

Nellie’s happiest days were spent with the love of her life, Bill Lawing, in their log cabin on the shores of beautiful Kenai Lake. She fondly mentions it in the opening paragraph of her autobiography, ‘Alaska Nellie’:

“Glancing out through an open window of a large log home on the shores of Kenai Lake at Lawing, Alaska, the rippling waves had become glittering jewels in the full moonlight of a summer’s night.

Mountains covered with evergreen trees and crowned with snow were reflected in the mirror-like water of Kenai Lake. Was I dreaming, or was the curtain of the past rolling up, so that I might glance back over twenty-four years spent in the great North-land and say, ‘No regrets.'”

In 1939 a short movie clip, ‘The Land of Alaska Nellie,’ was produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios:

Alaska Nellie’s grave is in the city cemetery in Seward, Alaska, a pretty place at the base of the mountains, guarded by towering Sitka spruce trees. Her gravestone bears the image of a pineapple, a symbol of hospitality which began with the sea captains of New England, who sailed among the Caribbean Islands and returned bearing cargos of fruits, spices and rum.

Alaska Nellie’s grave is in the city cemetery in Seward, Alaska, a pretty place at the base of the mountains, guarded by towering Sitka spruce trees. Her gravestone bears the image of a pineapple, a symbol of hospitality which began with the sea captains of New England, who sailed among the Caribbean Islands and returned bearing cargos of fruits, spices and rum.

According to tradition in the Caribbean, the pineapple symbolized hospitality, and sea captains learned they were welcome if a pineapple was placed by the entrance to a village. At home, the captain would impale a pineapple on a post near his home to signal friends he’d returned safely from the sea, and would receive visits. As the tradition grew popular, innkeepers added the pineapple to their signs and advertisements, and the symbol for hospitality was further secured as needle-workers preserved the image in family heirlooms such as tablecloths, doilies, potholders, door knockers, curtain finials and more. It seems a fitting final tribute to a legendary hostess of the north.

Nellie Lawing’s property on Kenai Lake, 1938.

For more information about Alaska Nellie, including resources for further reading and research and photos of her homesite in Lawing taken in recent years, visit the Northern Light Media website: Alaska Nellie | The Story of Nellie Neal Lawing

May-June, 2019 issue, Vol. 1, No. 1, postpaid

Articles include the construction of the Alaska Railroad; a 1918 trip by Margaret Murie, Addison Powell’s 1902 adventures in the Copper River Valley, the All Alaska Sweepstakes sled dog race, the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle, and the 1935 Matanuska Colony barns.

$12.00